What is object-oriented programming (OOP)?

Imagine applying for a new job and having to explain the term OOP. What is your answer to this question? In theory it is a paradigm that describes objects as instances of classes, their characteristics and behaviors. Apart from that OOP is mainly comprised of four design patterns, namely polymorphism, inheritance, abstraction and encapsulation. To put it simply it is often the goal to model relationships using an “is-a” relationship using inheritance.

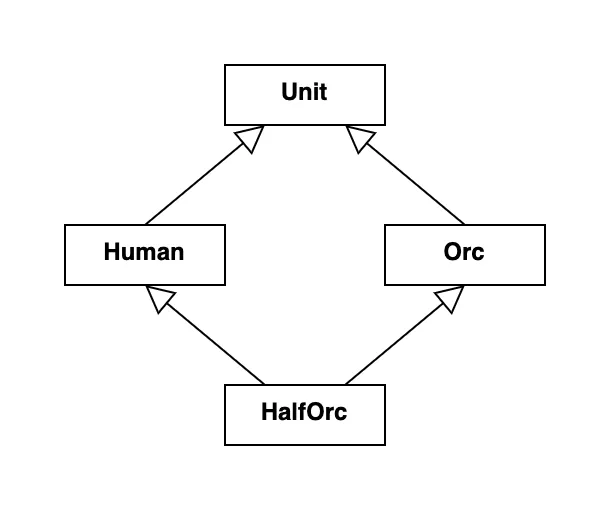

One of the most common pitfalls of inheritance is the so-called diamond problem, indicated by the following Java code:

abstract class Unit {

public abstract void speak();

}

class Human extends Unit {

@Override

public void speak() {

System.out.println("I'm a human.");

}

}

class Orc extends Unit {

@Override

public void speak() {

System.out.println("I'm an orc.");

}

}

// Not possible in Java since there is no multiple inheritance.

class HalfOrc extends Human, Orc {}

class Application {

public static void main(String[] args) {

var unit = new HalfOrc();

// What is the output of this?

unit.speak();

}

}In this context the term diamond problem refers to the shape we get when we sketch the relations between those classes.

Assuming that Java would allow multiple inheritance as denoted in the initial snippet it is ambiguous what the output of the call to speak() should be for an object of type HalfOrc.

Our attempt to abstract away the behavior of an entity into different subtypes isn’t possible using just abstract classes and we need different kinds of relations.

As such working within a domain that is built on multiple of those “is-a” relationships can become unruly if we attempt to create some unusual workarounds.

In order to prevent this and other caveats found in very classic OOP languages, Rust was built with a different philosophy, dropping inheritance entirely in favor of other patterns such as composition.

Composition isn’t a novel idea

The solution to the previously mentioned issue is to introduce “has-a” relationships over “is-a” relationships using the composite pattern for example. In all fairness I have to confess that this is by no means a new paradigm that Rust has established. It has always existed, even in the era of half-century-old coding practices, especially with the notion of interfaces enabling polymorphic behavior. Before we can check what idiomatic Rust code for composition and abstraction looks like we have to go over the basic syntax of classes first.

Let’s talk Rust

First let us start with the concept of structs within Rust and their declaration.

In other object-oriented languages custom data types are often named class and are usually comprised of multiple fields, functions and methods.

Rust on the other hand allows field definitions and function / method definitions to be separated.

The former are defined using the struct keyword while the latter are placed inside an implementation block.

/// Lightweight undirected graph defined by a set of edges rather than nodes

/// and edges.

struct Graph {

/// Edges contained within the graph modelled as tuples connecting

/// two `i32`.

edges: BTreeSet<(i32, i32)>,

}Our Graph struct contains a single field edges of type BTreeSet<(i32, i32)> and nothing more.

What is noticeable is that structs in Rust, unlike classes in other languages, strictly separate fields and functions.

Using implementation blocks starting with impl we can define functions and methods for our struct.

We can even freely group multiple functions within separate impl block and even have them in separate files.

This is common within the Rust ecosystem which uses feature flags to conditionally enable code blocks.

For the sake of readability we will split the following snippets into multiple impl blocks and discuss the different kinds of functions one at a time.

impl Graph {

/// Create a new Graph.

fn new() -> Self {

Self {

edges: BTreeSet::new(),

}

}

}Graph::new() is an associated function (static method in C# or Java) that can be invoked without an instance.

In fact, Rust doesn’t have classic constructors as other languages, but it is convention to have such a new() function which behaves like a constructor.

impl Graph {

/// Returns a boolean value indicating whether there exists an edge

/// between the two specified nodes.

fn contains_edge(&self, a: i32, b: i32) -> bool {

self.edges.contains(&(a, b))

}

}Graph::contains_edge() is an actual (instance) method indicated by the first parameter, namely &self (similar to Python or this in C# and Java).

An associated function like the previously shown Graph::new() has no such parameter.

The syntax &self is syntactic sugar for self: &Self which is a reference to the underlying instance.

In order to invoke that method it has be called using an existing instance as follows:

let graph = Graph::new();

// ... do something with graph

let result = graph.contains_edge(1, 2);Finally we’ll have a look at a slightly different kind of (instance) method that is defined in the following snippet:

impl Graph {

/// Adds a new edge between the two specified nodes.

fn add_edge(&mut self, a: i32, b: i32) {

self.edges.insert((a, b));

}

}Compared to Graph::contains_edge() the new method Graph::add_edge() operates on a mutable reference of self indicated by the &mut self as the first parameter.

The distinction between &self and &mut self really helps to not only document that (im)mutable nature of a method, it is also enforced by the compiler.

Here is a snippet that intentionally attempts to invoke Graph::add_edge() on an instance that is immutable:

// The instance of Graph is NOT marked as mut.

let graph = Graph::new();

graph.add_edge(1, 2);This snippet won’t compile and the compiler will error with the following message:

error[E0596]: cannot borrow `graph` as mutable, as it is not declared as mutable

--> src/main.rs:31:5

|

30 | let graph = Graph::new();

| ----- help: consider changing this to be mutable: `mut graph`

31 | graph.add_edge(1, 2);

| ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ cannot borrow as mutableAdditionally a method that mutates self but isn’t marked as such would also cause a compilation error:

// Notice that self isn't marked as mut.

fn add_edge(&self, a: i32, b: i32) {

// The BTreeSet::insert() method called here is marked as &mut self.

// Therefore Rust will know that add_edge is mutating.

self.edges.insert((a, b));

}Attempting to compile the previous snippet yields an error, that might be difficult to understand, but notice the suggestion it gives on how to resolve the issue:

error[E0596]: cannot borrow `self.edges` as mutable, as it is behind a `&` reference

--> src/lib.rs:14:9

|

13 | fn add_edge(&self, a: i32, b: i32) {

| ----- help: consider changing this to be a mutable reference: `&mut self`

14 | self.edges.insert((a, b));

| ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ `self` is a `&` reference, so the data it refers to cannot be borrowed as mutableWhat about composition?

After the introduction into the general syntax of structs and functions the question what composition looks like in Rust remains. The easiest approach to model composition is to nest structs into each other and delegate function calls respectively:

struct Human {

// ... some fields specific to humans

}

impl Human {

fn speak(&self) {

println!("I'm a human.");

}

}

struct Orc {

// ... some fields specific to orcs

}

impl Orc {

fn speak(&self) {

println!("I'm an orc.");

}

}

struct HalfOrc {

// Nest an instance of Human into this struct

human: Human,

// Nest an instance of Orc into this struct

orc: Orc,

// ... some fields specific to half orcs

}

impl HalfOrc {

fn speak(&self) {

// Explicitly do something here specific to the half-orc.

// Maybe it pretends to be both a human and an orc?

// We can delegate function calls to the nested instances.

self.human.speak();

self.orc.speak();

}

}Since this solution may not be the best in all scenarios we can consider the option of introducing abstraction using traits.

So, what does abstraction in Rust look like?

Abstraction within Rust is modelled using traits which are comparable to interfaces in C# and Java. The syntax is fairly self-explanatory:

/// A trait that exposes a method to speak depending on how this trait is implemented.

trait Speak {

fn speak(&self);

}

// A bunch of races.

struct Human;

struct Orc;

struct HalfOrc;

impl Speak for Human {

fn speak(&self) {

println!("I'm a human.");

}

}

impl Speak for Orc {

fn speak(&self) {

println!("I'm an orc.");

}

}

impl Speak for HalfOrc {

fn speak(&self) {

println!("I'm half human and half orc.");

}

}

/// Free function that takes a reference to any object that implements Speak.

fn let_unit_speak(unit: &impl Speak) {

unit.speak();

}

fn main() {

let_unit_speak(&Human); // prints "I'm a human."

let_unit_speak(&Orc); // prints "I'm an orc."

let_unit_speak(&HalfOrc); // prints "I'm half human and half orc."

}As you can see, every custom struct can freely implement a trait and provide their custom implementation details.

A function such as let_unit_speak does not care about the actual type of the supplied object, it only expects something that implements Speak.

In order to have some default behavior between types that implement a trait Rust allows for default implementations of methods within traits which can easily be overridden.

/// A trait that exposes a method to speak depending on how this trait is implemented.

trait Speak {

fn speak(&self) {

println!("I can speak.");

}

}

// A bunch of units.

struct Human;

struct Mime;

// Use the default implementation for Human.

impl Speak for Human {}

impl Speak for Mime {

fn speak(&self) {

// A good mime does not speak with actual words!

println!("*inaudible gestures*");

}

}

/// Free function that takes a reference to any object that implements Speak.

fn let_unit_speak(unit: &impl Speak) {

unit.speak();

}

fn main() {

let_unit_speak(&Human); // prints "I can speak."

let_unit_speak(&Mime); // prints "*inaudible gestures*"

}Fun with traits: From and Into

A very interesting usage of traits is the combination of From and Into which are used for value-to-value conversion.

The most common usage of From is to implement how a type A can be converted to a type B by implementing From<A> for B.

This implementation allows to manually convert A to B using B::from().

On top of that the Rust standard library provides a blanket implementation of Into<B> for A for every From<A> for B.

Said implementation exposes an A::into() method that automatically calls B::from() that we implement ourselves.

Those two traits often appear in tandem when a function has a parameter of a certain type, but should be designed to accept anything else that can be converted into that correct type as well. In code this looks as follows:

/// A custom struct which only wraps a single integer value.

struct Number {

value: i32,

}

// The implementation of this trait describes how any i32 can be converted into a Number.

impl From<i32> for Number {

// In this case Self refers to Number, the type for which we implement this trait.

fn from(value: i32) -> Self {

// This "conversion" is trivial as value is already an i32.

Self { value }

}

}

// The implementation of this trait describes how any f32 can be converted into a Number.

impl From<f32> for Number {

fn from(value: f32) -> Self {

Self {

// We must convert the f32 to an i32 by rounding it.

value: value.round() as i32,

}

}

}

/// A free function that expects anything that can be converted into Number.

// Remember that we don't need to implement Into ourselves. Every From we implement for

// Number automatically has a corresponding Into.

fn expects_number(numberlike: impl Into<Number>) {

// The into method performs the conversion to Number and uses the Number::from()

// methods declared in the previous implementations of the From trait.

let number = numberlike.into();

println!("Number Value: {}", number.value);

}

fn main() {

expects_number(Number { value: 1 }); // prints "Number Value: 1"

expects_number(2); // prints "Number Value: 2" using the From<i32> implementation

expects_number(3.14); // prints "Number Value: 3" using the From<f32> implementation

}As you can see, using traits as a means of abstraction it is possible to introduce behavior for functions to handle polymorphic data.